Patients with Hip Pain are seen quite frequently in our daily practice and most of them can be managed very efficiently in outdoor clinics. Identifying the source and mechanism of the pain to determine proper treatment is usually not difficult. Hip pain can originate from intraarticular, extraarticular or referred source of pain from neighbouring joints like spine, sacroiliac joints and knee.

The anatomy of the hip

The hip joint creates the jointed connection between the trunks and the legs. It connects the pelvis and thigh bones. It is a ball-and socket joint, which, due to its shape, enables great freedom of movement. It consists of a socket of the hip bone (pelvic bone) and a condyle (thigh bone), which is covered with a layer of cartilage.

The joint itself is sealed off by a joint capsule. Within the joint capsule, a mucosa layer produces the synovial fluid, which on one hand nourishes the cartilage, and on the other hand produces friction free sliding. The synovial fluid also serves as a sort of shock absorber which intercepts the powerful force that impinge on the joint during a person’s lifetime. The bones are connected by the ligaments, which impart the necessary stability to the joint. The joint is moved by muscles and tendons.

Common causes of Hip pain

Childhood disorders

|

Trauma

|

Inflammation

|

Infection

|

Neurologic

|

Vascular

|

| Degenerative Arthritis / Osteoarthritis | Neoplasm – Benign and malignant tumours of hip including multiple myeloma |

Hormonal & metabolic causes

|

Other cases

|

Differential diagnosis of hip pain

The goal of differential diagnosis of hip pain is to identify the location and underlying mechanism of pain. An accurate history and physical examination may indicate the location and site of origin. Laboratory or imaging studies may be necessary to determine the exact cause. Fracture, infection and ischemic necrosis should be ruled out early because they may require immediate treatment to prevent further damage to the joint.

History

A thorough history of hip pain can narrow the differential diagnosis; sometimes it can give a conclusive diagnosis. Hip pain of sudden onset suggests trauma; overstretch, overstrain, or overuse injuries; or acute inflammation or infection. Trauma can tear the labrum and cause other intraarticular damage. Overstretch, overstrain and overuse injuries to the soft tissues may cause tendonitis or bursitis. Acute pain over the greater trochanter usually indicates bursitis.

Hip pain secondary to synovial inflammation can be caused by RA or by a spondyloarthropathy. Infections of the hip are usually found in early childhood and may indicate septic arthritis, tubercular arthritis or transient synovitis and they can destroy the joint along with adjacent bone rapidly.

Intermittent pain, especially unilateral pain radiating from the groin downs the anterior thigh; usually indicate an intraarticular problem, including ischemic necrosis of the involved hip.

Chronic hip pain, perhaps accompanied by a gradual loss of function over a period of years, is more likely to be secondary to osteoarthrosis from prior trauma or hip dysplasia, osteochondral injury, or overuse syndrome in the young athlete.

Pain may be referred to the hip from the lumbar region in patients with radiculopathy, a knee disorder, or a sacroilitis. Pain often is referred from the hip to the lumbar spine, groin, buttock, anterior medial thigh, or knee.

Pain that limits internal or external rotation, flexion, extension, or abduction of the hip usually is associated with intraarticular disorders.

Activities that worsen or lessen pain also can offer clues to the diagnosis. Pain worsens with weight-bearing and activity that improves with rest is typical of OA. Morning stiffness or stiffness that appears after a long period of inactivity and lasts at least an hour is more common in RA. Young patients of early 20s presenting morning stiffness, back pain and pain in the larger joints should be suspected for ankylosing spondylitis.

Physical Findings

The physical examination should include an analysis of the patient’s gait, range of motion, specific areas of tenderness, deformities, swelling and muscle wasting around hip. In extraarticular pathology pain and tenderness will be in one particular part of hip and movement in only one or two direction is limited. Whereas in intraarticular pathology, tenderness is present all around the hip and mostly movement is restricted in all directions especially rotations.

The painful gait can indicate a functional abnormality in the hip, pelvis, or low back. A slight limp accompanied by hip pain is a common presenting sign and can be evidence of dysplasia. Snapping hip can have either intraarticular or extraarticular causes. Extraarticular causes include iliopsoas and iliotibial band syndromes. In iliopsoas syndrome, the movement of the iliopsoas tendon over the femoral head when the hip moves from extension to flexion causes the snapping sound.

Reduced range of motion usually indicates an intraarticular problem, such as OA, ischemic necrosis, inflammatory synovitis, infections or a labral tear. Discrepancy in limb length with painful hip is a very positive sign of erosion of acetabulum or collapse and degeneration of femoral head. Muscle spasm around the hip is a sign of active inflammatory or infective disease of the hip. Instability of hip can be demonstrated in fractures of acetabulum and femoral head, CDH and Perthes disease.

Laboratory Examination

Analyses of blood, urine and synovial fluid can refine the diagnosis, especially when inflammation or infection is suspected as the cause of pain.

Leukocytosis may indicate infection. Anemia and thrombocytosis suggest chronic inflammation usually associate with RA. Elevated serum urea and serum creatinine levels suggest renal disease that may be associated with SLE or chronic renal failure. Elevated liver enzymes may indicate alcoholism in a patient with ischemic necrosis of the hip. Sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein and serum Ig levels typically are

elevated in patients with inflammatory or infectious arthritis.

The HLA-B27 is associated with spondyloarthropathies and ankylosing spondylitis. More than 90% of patients with ankylosing spondylitis test positive for this gene. Symptoms often appear in patients in their teens and early 20s and often are missed or attributed to trauma or other causes. Although the antinuclear antibody test is positive in 95% of cases of SLE. Rheumatoid factor is present in 80% of patients with RA.

Synovial fluid analysis can differentiate inflammatory and infective arthritis.

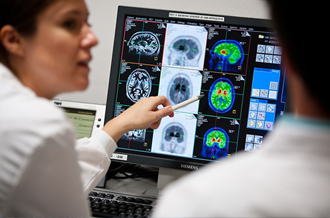

Imaging-Studies

Several non-invasive and invasive medical imaging technologies are available for evaluating hip pain. Plain radiography can image gross fractures and effusions, but most of the minor hip fractures and infections are usually missed by plain X-Rays. Computed tomography with 3D reconstruction provides detail of bone fragments in comminuted and displaced fractures, but it misses the more common trabecular bone injuries and marrow edema in early stages of hip pathology. Bone scan is more sensitive for trabecular bone injuries and osteomyelitis than CT scanning, but it is limited by lack of specificity. Bone scans now are limited to evaluating disorders that are likely to involve multiple skeletal locations, such as metastatic disease. Magnetic resonance imaging is more sensitive and specific than bone scans for traumatic and inflammatory diseases of the hip and is now the diagnostic modality of choice for evaluating significant hip pain including early stages of ischemic necrosis.

Osteoarthrosis may be diagnosed with plain radiography, but the other causes of chronic hip pain require MRI for optimal evaluation. Magnetic resonance arthrography best detects labral tears.

Ultrasound is valuable in diagnosing hip diseases in neonates, infants and children for synovitis with effusion, septic arthritis, congenital dislocation of the hip, perthes disease and slipped capital femoral epiphases. However its use is limited in evaluating soft tissues around the hip in young adults.

Medical treatment of hip pain

A common problem in treating hip pain is the lack of a clear diagnosis. Too often, the pain is attributed to a muscle strain, analgesics or NSAIDs are prescribed, and the patient is sent home. However, it is important to make a diagnosis, even if only a provisional one, to establish what the time and treatment course is likely to be.

fracture may require more specific treatment including surgery. Rheumatological and spondyloarthropathies may not respond to non specific treatment and should be managed by more specific disease modifying drugs, physiotherapy and traction.

Avascular necrosis, advanced arthritis and mechanical disorders may not respond to the medical treatment.

When specialist care is needed

Pain not responding to conservative treatment

X-ray changes suggestive of infection, avascular necrosis, osteoarthrosis

Changes in MRI with evidence of avascular necrosis and labral tear

CT Scan showing evidence of intraarticular fractures of femoral head or acetabulum

Late degenerative changes following CDH, Perthes, SUFE and AVN

Osteolytic legions / bone tumours of hip

When a patient has not responded appropriately to treatment, reconsider the diagnosis. Infections and